Finding representative samples efficiently for large datasets

by Avinash Mallya

Premise

In this day and age, we’re not short on data. Good data, on the other hand, is very valuable. When you’ve got a large amount of improperly labelled data, it may become hard to find to find a representative dataset to train a model on such that it generalizes well.

Let’s formalize the problem a little so that a proper approach can be developed. Here’s the problem statement:

- You have a large-ish set of (imperfectly) labelled data points. These data points can be represented as a 2D matrix.

- You need to train a model to classify these data points on either these labels, or on labels dervied from imperfect labels.

- You need a good (but not perfect) representative sample for the model to be generalizable, but there are too many data points for each label to manually pick representative examples.

In a hurry?

Here’s what you need to do:

- Read the premise and see if it fits your problem.

- Go to the For the folks in a hurry! section at the end to find the generic solution and how it works.

Why do we need representative samples?

Generally, three things come to mind:

- Allows the model to be generalizable for all kinds of data points within a category.

- Allows for faster training of the model - you need fewer data points to get the same accuracy!

- Allows maintaining the training set - if your training set needs validation by experts or annotations, this keeps your costs low!

Define the data

This data can be practically anything that can be represented as a 2D matrix.

There are exceptions. Raw image data (as numbers) might get difficult because even if you flatten them, they’ll be significant correlation between features. For example, a face can appear practically anywhere in the image, and all pixels centered around the face will be highly correlated, even if they are on different lines. A workaround in this case would be to pipe the image through a CNN model that has been trained on some generic task and produces a 1D representation of a single image in the final hidden layer before the output. Other data will need further processing along similar lines.

Get a specific dataset

For this specific article, I will use the ShopMania dataset on Kaggle. I apologize in advance for not using a more easily accessible dataset (you need to sign into Kaggle to download it) - and I’m not 100% sure if the GPL allows me to create a copy of the data and place it in my own repository. Nevertheless, the data (if you download it and choose to use it instead of some other dataset) will look like this:

NOTE: whenever I want to show an output along with the code I used for it, you’ll see the characters

>>indicating the command used, and the output to be without those prefixes.

>> import polars as pl

>> data = pl.read_csv("archive/shopmania.csv")

>> data

shape: (313_705, 4)

┌────────────┬──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┬─────────────┬────────────────┐

│ product_ID ┆ product_title ┆ category_ID ┆ category_label │

│ --- ┆ --- ┆ --- ┆ --- │

│ i64 ┆ str ┆ i64 ┆ str │

╞════════════╪══════════════════════════════════════════════════════╪═════════════╪════════════════╡

│ 2 ┆ twilight central park print ┆ 2 ┆ Collectibles │

│ 3 ┆ fox print ┆ 2 ┆ Collectibles │

│ 4 ┆ circulo de papel wall art ┆ 2 ┆ Collectibles │

│ 5 ┆ hidden path print ┆ 2 ┆ Collectibles │

│ … ┆ … ┆ … ┆ … │

│ 313703 ┆ deago anti fog swimming diving full face mask ┆ 229 ┆ Water Sports │

│ ┆ surface snorkel scuba fr gopro black s/m ┆ ┆ │

│ 313704 ┆ etc buys full face gopro compatible snorkel scuba ┆ 229 ┆ Water Sports │

│ ┆ diving mask blue large/xtralarge blue ┆ ┆ │

│ 313705 ┆ men 039 s full face breathe free diving snorkel mask ┆ 229 ┆ Water Sports │

│ ┆ scuba optional hd camera blue mask only adult men ┆ ┆ │

│ 313706 ┆ women 039 s full face breathe free diving snorkel ┆ 229 ┆ Water Sports │

│ ┆ mask scuba optional hd camera black mask only ┆ ┆ │

│ ┆ children and women ┆ ┆ │

└────────────┴──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┴─────────────┴────────────────┘

The data documentation on Kaggle states:

The first dataset originates from ShopMania, a popular online product comparison platform. It enlists tens of millions of products organized in a three-level hierarchy that includes 230 categories. The two higher levels of the hierarchy include 39 categories, whereas the third lower level accommodates the rest 191 leaf categories. Each product is categorized into this tree structure by being mapped to only one leaf category. Some of these 191 leaf categories contain millions of products. However, shopmania.com allows only the first 10,000 products to be retrieved from each category. Under this restriction, our crawler managed to collect 313,706 products.

For demonstration, I’ll just limit the categories to those that have exactly 10,000 occurences.

data = (

data

.filter(pl.count().over("category_ID") == 10000)

)

You’ll notice that there are only 17 categories in this dataset. Run this to verify that fact.

>>> data.get_column("category_label").unique()

shape: (17,)

Series: 'category_label' [str]

[

"Kitchen & Dining"

"Scarves and wraps"

"Handbags & Wallets"

"Rugs Tapestry & Linens"

"Cell Phones Accessories"

"Men's Clothing"

"Jewelry"

"Belts"

"Men Lingerie"

"Crafts"

"Football"

"Medical Supplies"

"Adult"

"Hunting"

"Women's Clothing"

"Pet Supply"

"Office Supplies"

]

Note that this is very easy in Polars, which is the package I typically use for data manipulation. I recommend using it over Pandas.

Specify the task

Okay - so now we have exactly 10,000 products per category. We only have the title of the product that can be leveraged for categorization. So let me define the task this way:

Craft a small representative sample for each category.

Why small? It helps that it’ll make the model faster to train - and keep the training data manageable in size.

Finding representative samples

I mentioned earlier that we need to represent data as a 2D matrix for the technique I have in mind to work. How can I translate a list of text to a matrix? The answer’s rather simple: use SentenceTransformers to get a string’s embedding. You could also use more classic techniques like computing TF-IDF values, or use more advanced transformers, but I’ve noticed that SentenceTransformers are able to capture semantic meaning of sentences rather well (assuming you use a good model suited for the language the data is in) - they are trained on sentence similarity after all.

Getting SentenceTransformer embeddings

This part is rather simple. If you’re unable to install SentenceTransformers, please check their website.

import sentence_transformers

# See list of models at www.sbert.net/docs/pretrained_models.html

ST = sentence_transformers.SentenceTransformer("all-mpnet-base-v2")

title_embeddings = (

ST.encode(

data.get_column("product_title").to_list(),

show_progress_bar=True, convert_to_tensor=True)

.numpy())

This process will be slow (~30 minutes) if you don’t have a GPU. There are faster approaches, but they are slightly more involved than would be beneficial for a blog post. The wait will be worth it, I promise! In addition, the call to .numpy() at the end is to directly get a single numpy array - otherwise you get a list of numpy arrays, which is rather inefficient. Further, SentenceTransformers will try to run on the GPU if available, and if so, you will need to write .cpu().numpy() so that the tensor is copied from the GPU to the CPU.

NOTE: for a proof-of-concept implementation, or if you’re on the CPU, try the

all-MiniLM-L6-v2model. It’s a much smaller and much faster model, although you sacrifice a little in terms of accuracy.

The concept of approximate nearest neighbors

Performing any kind of nearest neighbor algorithm on medium scale datasets (even bordering 10,000 rows and tens of columns) tends to be slow. A primary driver of this was the need to calculate all, or nearly all distances between all data points. Approximate nearest neighbor (ANN) algorithms work around this through various approaches, which warrant their own blog post. For now, it would suffice to understand that there are shortcuts that ANN algorithms take to give you if not the exact nearest neighbor, at least one of the nearest neighbors (hence the term approximate).

There are several algorithms that you can use - I shall proceed with faiss, because it has a nice Python interface and is rather easy to work with. You can use any algorithm - a full list of the major ones are available here.

I’ll explain why we’re in the nearest neighbor territory in due course.

Building the database

To build the database, all we need is the title_embeddings matrix.

import faiss

def create_index(title_embeddings):

d = title_embeddings.shape[1] # Number of dimensions

ann_index = faiss.IndexFlatL2(d) # Index using Eucledian Matrix

ann_index.add(title_embeddings) # Build the index

return ann_index # Faiss considers databases an "index"

This does create a database. But remember, we’re trying to find representative samples - which means we need to do this by the category (or label). So let’s design a function that sends only the necessary data as that for a particular category, and then create the database. We’ll need three pieces of information from this function:

- The actual

faissdatabase. - The actual subset of data that was used to build this index.

- The label indices with respect to the original data that went into the

faissdatabase.

(2) and (3) will help us later in rebuilding a “network graph” that will allow us to reference the original data points.

import faiss

import numpy as np

import polars as pl

def create_index(label):

faiss_indices = (

data # this needs to be an argument if you want to create a generic function

.with_row_count("row_idx")

.filter(pl.col("category_label") == label)

.get_column("row_idx")

.to_list()

)

faiss_data = title_embeddings[faiss_indices]

d = data.shape[1] # Number of dimensions

faiss_DB = faiss.IndexFlatIP(d) # Index using Inner Product

faiss.normalize_L2(data) # Normalized L2 with Inner Product search = cosine similarity

# Why cosine similarity? It's easier to specify thresholds - they'll always be between 0 and 1.4.

# If using Eucledian or other distance, we'll have to spend some time finding a good range

# where distances are reasonable. See https://stats.stackexchange.com/a/146279 for details.

faiss_DB.add(data) # Build the index

return faiss_DB, faiss_data, faiss_indices

Identifying the nearest neighbors

To proceed with getting a representative sample, the next step is to find the nearest neighbors for all data points in the database. This isn’t too hard - faiss index objects have a built-in search method to find the k nearest neighbors for a given index, along with the (approximate) distance to it. Let’s then write a function to get the following information: the label index for whom nearest neighbors are being searched, the indices of said nearest neighbors and the distance between them. In network graph parlance, this kind of data is called an edge list i.e. a list of pair of nodes that are connected, along with any additional information that specifies a property (in this case distance) of the edge that connects these nodes.

def get_edge_list(label, k=5):

faiss_DB, faiss_data, faiss_indices = create_index(label)

# To map the data back to the original `train[b'data']` array

faiss_indices_map = {i: x for i,x in enumerate(faiss_indices)}

# To map the indices back to the original strings

title_name_map = {i: x for i,x in data.select("row_idx", "product_title").rows()}

distances, neighbors = faiss_DB.search(faiss_data, k)

return (

pl.DataFrame({

"from": faiss_indices})

.with_columns(

pl.Series("to", neighbors),

pl.Series("distance", distances))

.explode("to", "distance")

.with_columns(

pl.col("from")

.map_dict(title_name_map),

pl.col("to")

.map_dict(faiss_indices_map)

.map_dict(title_name_map))

.filter(pl.col("from") != pl.col("to"))

)

NetworkX and Connected Components

The next step in the process is to create a network graph using the edge-list. But why?

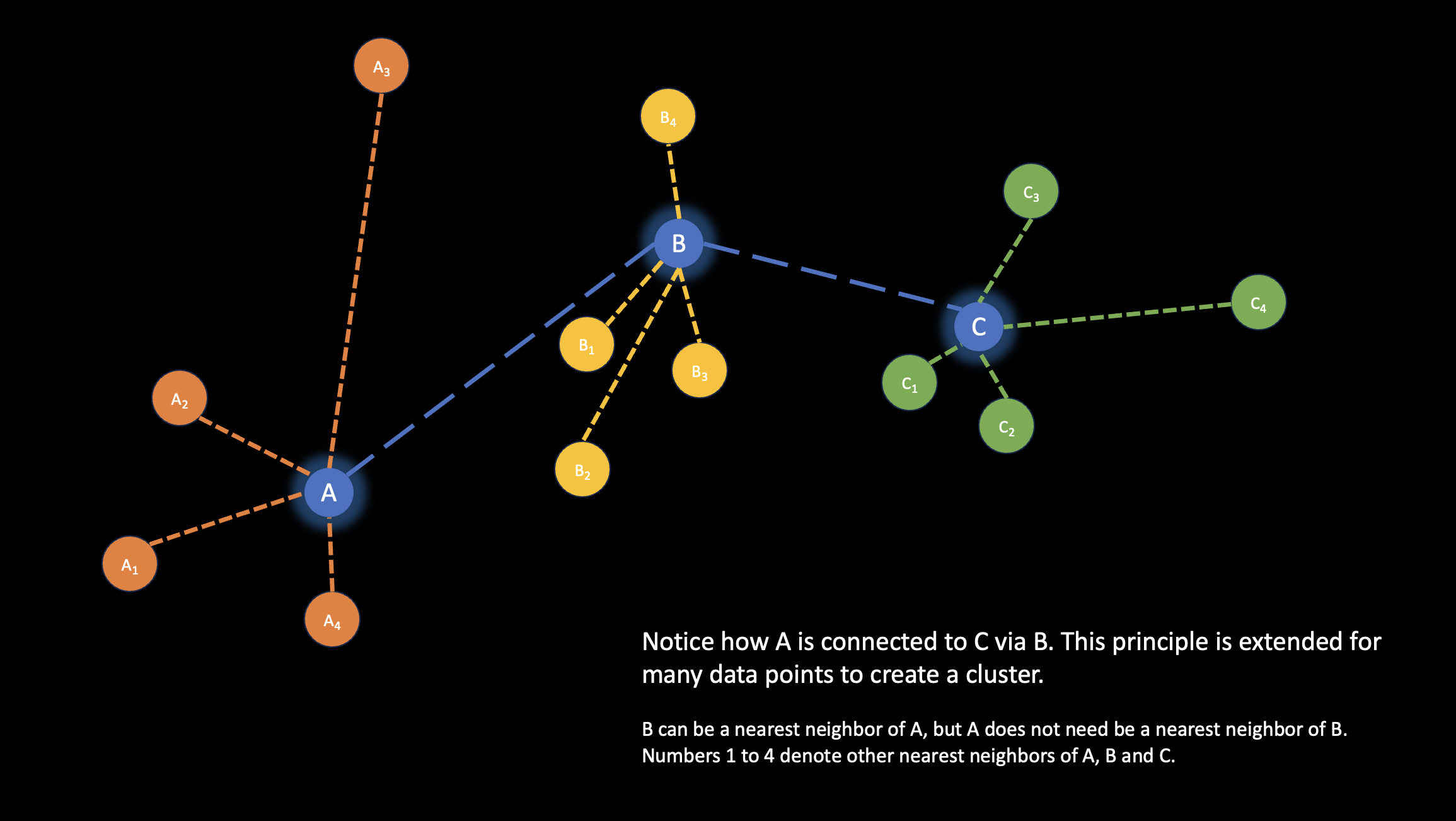

Remember that we have identified the (k=5) nearest neighbors of each data point. Let’s say that we have a point A that has a nearest neighbor B. C is not a nearest neighbor of A, but it is a nearest neighbor of B. In a network graph, if A and C are sufficiently similar enough to B within a particular minimum thershold, then A will be connected to C through B! Hopefully a small visual below would help.

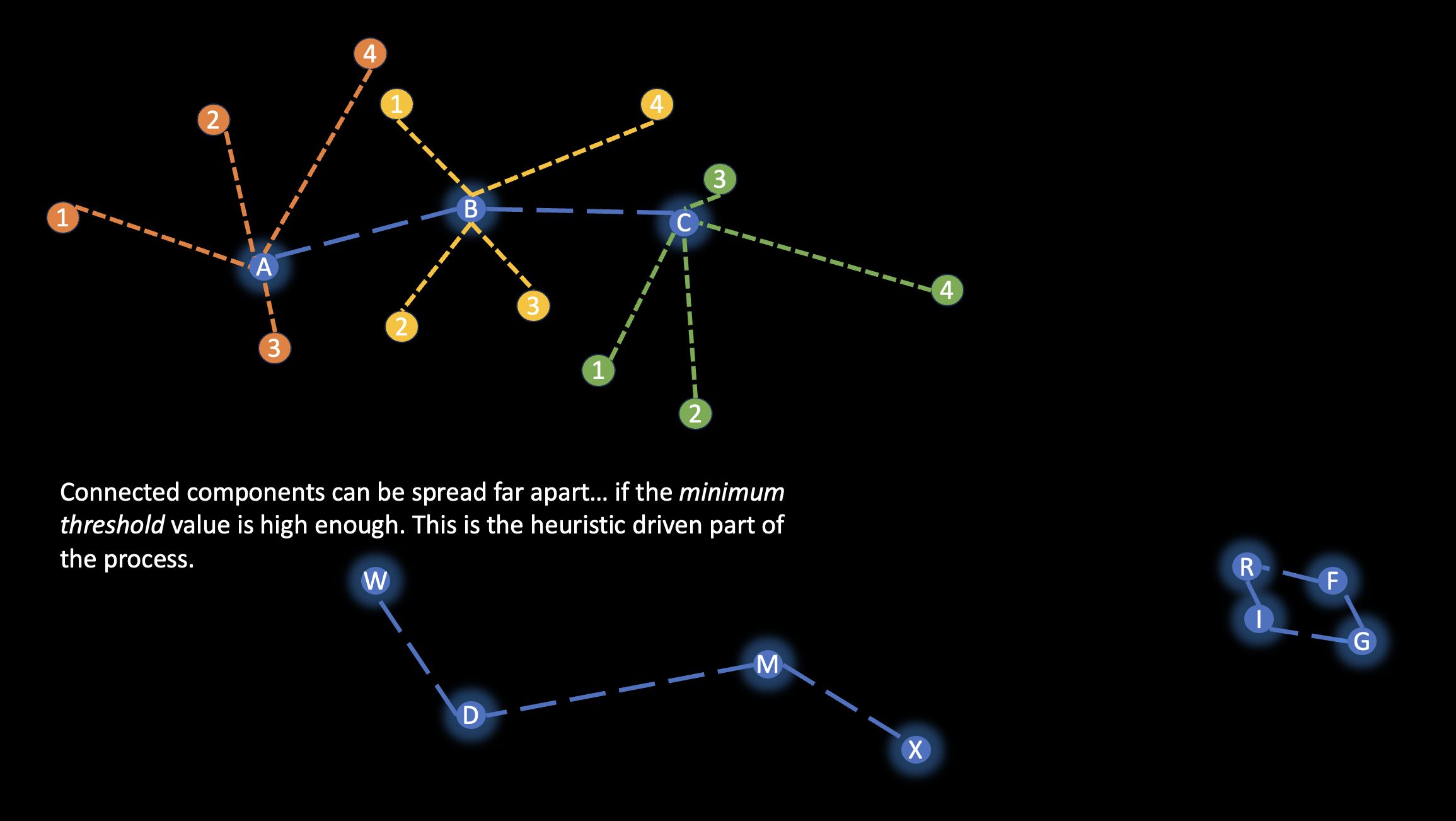

What happens when such a concept is extended for many data points? Not all of them would be connected - because we’re applying a minimum threshold that they have to meet. This is the only hueristic part of the rather fast process. Here’s one more helpful visual:

Very starry night-eque vibes here. Let’s get to the code.

import networkx as nx

def get_cluster_map(label, k=5, min_cosine_distance=0.95):

edge_list = (

get_edge_list(label, k=k)

.filter(pl.col("distance") >= min_cosine_distance)

)

graph = nx.from_pandas_edgelist(edge_list.to_pandas(), source="from", target="to")

return {i: list(x) for i,x in enumerate(nx.connected_components(graph))}

Getting clusters

Now that all the parts of the puzzle are together, let’s run it to see what kind of clusters you get for Cell Phone Accessories.

clusters = get_cluster_map("Cell Phones Accessories", 5, 0.95)

Make sure to configure the following if your results aren’t good enough:

- Relax the

min_cosine_distancevalue if you want bigger clusters. - Increase the number of nearest neighbors if you want more matches.

Viewing the components

There will likely be many clusters (you can see how many exactly with len(clusters)). Let’s look at a random cluster:

>> clusters[3]

['smartphone lanyard with card slot for any phone up to 6 yellow 72570099',

'smartphone lanyard with card slot for any phone up to 6 black 72570093',

'smartphone lanyard with card slot for any phone up to 6 lightblue 72570097',

'smartphone lanyard with card slot for any phone up to 6 blue 72570095',

'smartphone lanyard with card slot for any phone up to 6 green 72570101',

'smartphone lanyard with card slot for any phone up to 6 pink 72570091']

Let’s see another cluster that had 172(!) members in my run (the clusters themselves will be stable, but their indices may change in each run owing to some inherent randomness in the process).

>>> clusters[6]

['otm essentials iphone 8/7 modern clear printed phone case snowflakes iphone 8/7 op qq z051a',

'otm essentials iphone 8/7 modern clear printed phone case iphone 8/7 arrows blue op qq a02 58',

'otm essentials iphone 8/7/6s clear printed phone case single iphone 8/7/6s golden pineapple op qq z089a',

'otm essentials iphone 8/7/6s clear printed phone case single iphone 8/7/6s butteryfly delight yellow op qq z029d',

'otm essentials iphone 8/7 modern clear printed phone case iphone 8/7 luck of the irish op qq a01 45',

'otm essentials iphone 8/7 modern clear printed phone case iphone 8/7 brides maid white op qq a02 16',

...

'otm essentials iphone 8/7 modern clear printed phone case iphone 8/7 flying arrows white op qq hip 20',

'otm essentials iphone 8/7 modern clear printed phone case iphone 8/7 brides maid pink white op qq a02 17',

'otm essentials iphone 8/7 modern clear printed phone case iphone 8/7 anemone flowers white op qq z036a',

'otm essentials iphone 8/7 modern clear printed phone case mustache iphone 8/7 op qq hip 08',

'otm essentials iphone 8/7 modern clear printed phone case oh snap iphone 8/7 op qq z053a',

'otm essentials iphone 8/7/6s clear printed phone case single iphone 8/7/6s desert cacti orange pink op qq a02 22']

Running for all categories

This isn’t that hard (although it may take more than a moment). Just iterate it for each category!

clusters = [get_cluster_map(x, 5, 0.95) for x in data.get_column("category_label").unique()]

For the folks in a hurry!

I get it - you often want a solution that “just works”. I can come close to it. See below for code and a succinct explanation. For those of my readers who aren’t in a hurry, this also serves as a nice summary (and copy-pastable code)!

The code

import sentence_transformers

import faiss

import polars as pl

import numpy as np

# Data is read here. You download the files from Kaggle here:

# https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/lakritidis/product-classification-and-categorization

data = pl.read_csv("archive/shopmania.csv", new_columns=[

"product_ID", "product_title", "category_ID", "category_label"])

data = (

data

.filter(pl.count().over("category_ID") == 10000)

.with_row_count("row_idx")

)

# See list of models at www.sbert.net/docs/pretrained_models.html

ST = sentence_transformers.SentenceTransformer("all-mpnet-base-v2")

title_embeddings = (

ST.encode(

data.get_column("product_title").to_list(),

# I'm on a MacBook, you should use `cuda` or `cpu`

# if you've got different hardware.

device="mps",

show_progress_bar=True, convert_to_tensor=True)

.cpu().numpy())

# Code to create a FAISS index

def create_index(label):

faiss_indices = (

data # this needs to be an argument if you want to create a generic function

.filter(pl.col("category_label") == label)

.get_column("row_idx")

.to_list()

)

faiss_data = title_embeddings[faiss_indices]

d = faiss_data.shape[1] # Number of dimensions

faiss_DB = faiss.IndexFlatIP(d) # Index using Inner Product

faiss.normalize_L2(faiss_data) # Normalized L2 with Inner Product search = cosine similarity

faiss_DB.add(faiss_data) # Build the index

return faiss_DB, faiss_data, faiss_indices

# Code to create an edge-list

def get_edge_list(label, k=5):

faiss_DB, faiss_data, faiss_indices = create_index(label)

# To map the data back to the original `train[b'data']` array

faiss_indices_map = {i: x for i,x in enumerate(faiss_indices)}

# To map the indices back to the original strings

title_name_map = {i: x for i,x in data.select("row_idx", "product_title").rows()}

distances, neighbors = faiss_DB.search(faiss_data, k)

return (

pl.DataFrame({

"from": faiss_indices})

.with_columns(

pl.Series("to", neighbors),

pl.Series("distance", distances))

.explode("to", "distance")

.with_columns(

pl.col("from")

.map_dict(title_name_map),

pl.col("to")

.map_dict(faiss_indices_map)

.map_dict(title_name_map))

.filter(pl.col("from") != pl.col("to"))

)

# Code to extract components from a Network Graph

import networkx as nx

def get_cluster_map(label, k=5, min_cosine_distance=0.95):

edge_list = (

get_edge_list(label, k=k)

.filter(pl.col("distance") >= min_cosine_distance)

)

graph = nx.from_pandas_edgelist(edge_list.to_pandas(), source="from", target="to")

return {i: list(x) for i,x in enumerate(nx.connected_components(graph))}

# Example call to a single category to obtain its clusters

clusters = get_cluster_map("Cell Phones Accessories", 5, 0.95)

# Example call to **all** categories to obtain all clusters

clusters = [get_cluster_map(x, 5, 0.95) for x in data.get_column("category_label").unique()]

How the code works

If you want to write down an algorithmic way of looking at this approach,

- Obtain a 2D representation of the labelled/categorized data. This can be embeddings for strings, the final hidden state output from a generic CNN model for images, or a good ol’ tabular dataset where all numbers are normalized and can be expressed as such.

- Create an ANN database (based on a package such as

faiss) that allows you fast nearest neighbor searches. Use cosine similarity for an easy threshold determination step. - Obtain an edge-list of k (from 5 to 100) nearest neighbors for all (or a sample of data points in case your dataset is incredibly HUGE) data points in the ANN database.

- Apply a minimum threshold on similarity (completely based on heuristics), and obtain the connected components of the network graph from the filtered edge-list you just created.

- Map all indices back to their source data-points that make sense, and pick any number of items from each cluster (usually, I end up picking one element from each cluster), and you now have your representative sample!